| Condition | Mean | N | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

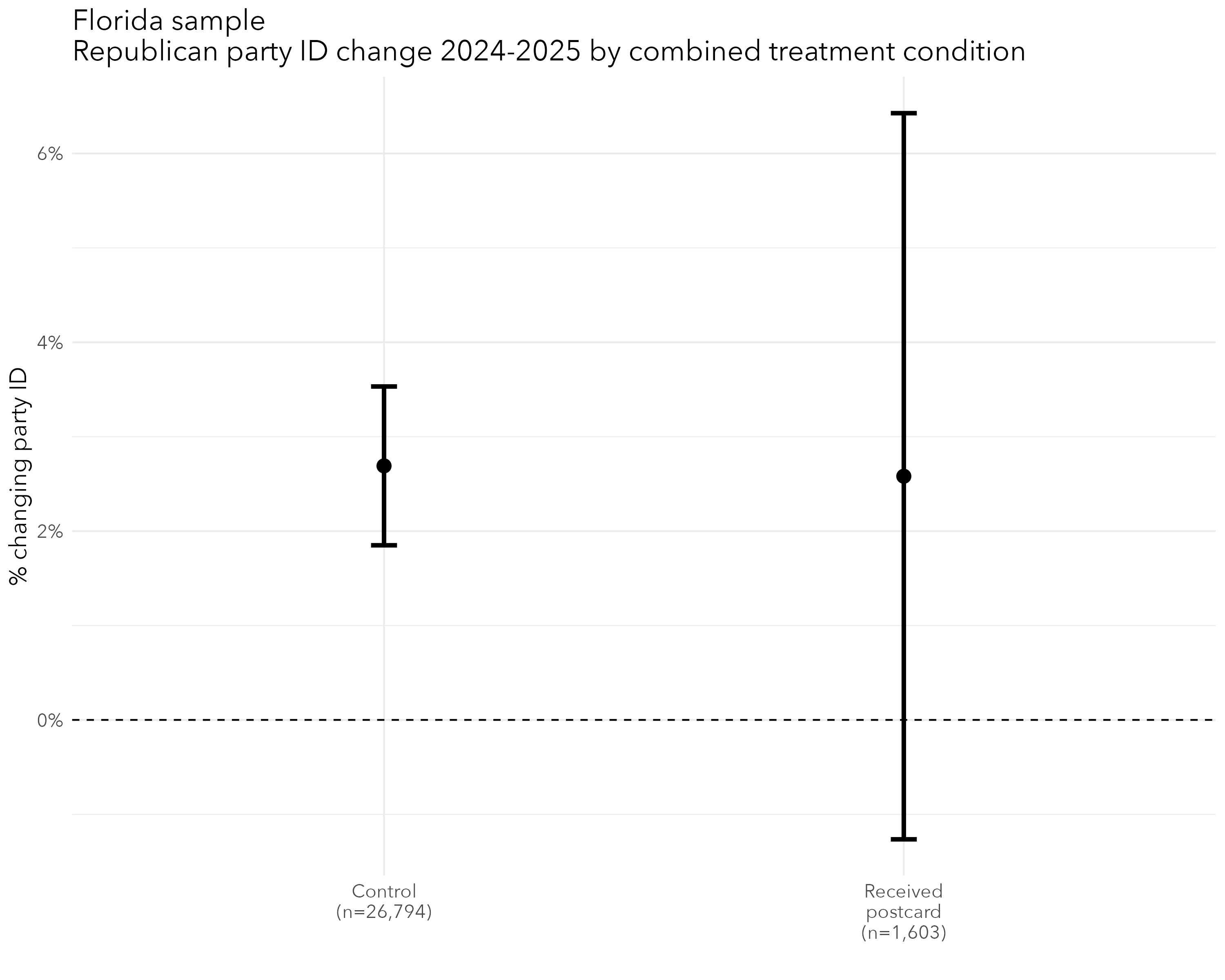

| Did not receive postcard | 2.7% | 26,794 | 0.8% |

| Received postcard | 2.6% | 1,603 | 3.9% |

In the 2024 election cycle I designed and implemented a couple of experiments to measure the impact of postcards on voters’ behavior. In one experiment, I sent postcards containing different messages to low-propensity Republican voters to attempt to reduce their turnout and induce them to reconsider their party affiliation. In a second experiment, I sent poscards to low-propensity Democratic voters to see if different types of postcards could induce turnout. In this post, I summarize the results of these experiments.

Postcards to low-propensity Republicans did not meaningfully impact their party affiliation nor their turnout behavior. Handwritten postcards to low-propensity Democratic voters were no more or less effective than typed postcards or than “facsimile handwritten” postcards, i.e., postcards where a handwritten message was copied onto many postcards.

Experiment 1: Postcards to low-turnout, non-primary participating Republican voters in Florida and Pennsylvania red districts

The design for this experiment is described in this post. To quickly summarize – the sample universe for this study included low-turnout Republican voters living in “red” areas of the key battleground states of Pennsylvania and Florida. To be in the sample universe for this experiment, the Florida and Pennsylvania voters had to…

- Reside in a “fully red” precinct, as defined above

- Be registered Republican

- Be marked as “active” on the voterfile

- Have full address information on the voterfile including zip code

- Have voted in 2016 but not 2020

- Not vote in primaries per vote history data available on the voterfile

Generally, these criteria were meant to capture Republicans who might’ve been “sour on the brand” (i.e., they voted for Trump once, but not twice), and to exclude those who were involved enough to participate in Republican primaries. Because the experiment involved talking to Republicans, which risked producing backlash, the sample geography in each state was limited to “red precincts” - i.e., precincts represented by Republicans at the state legislative and Congressional levels, and that on net voted for Trump in 2020.

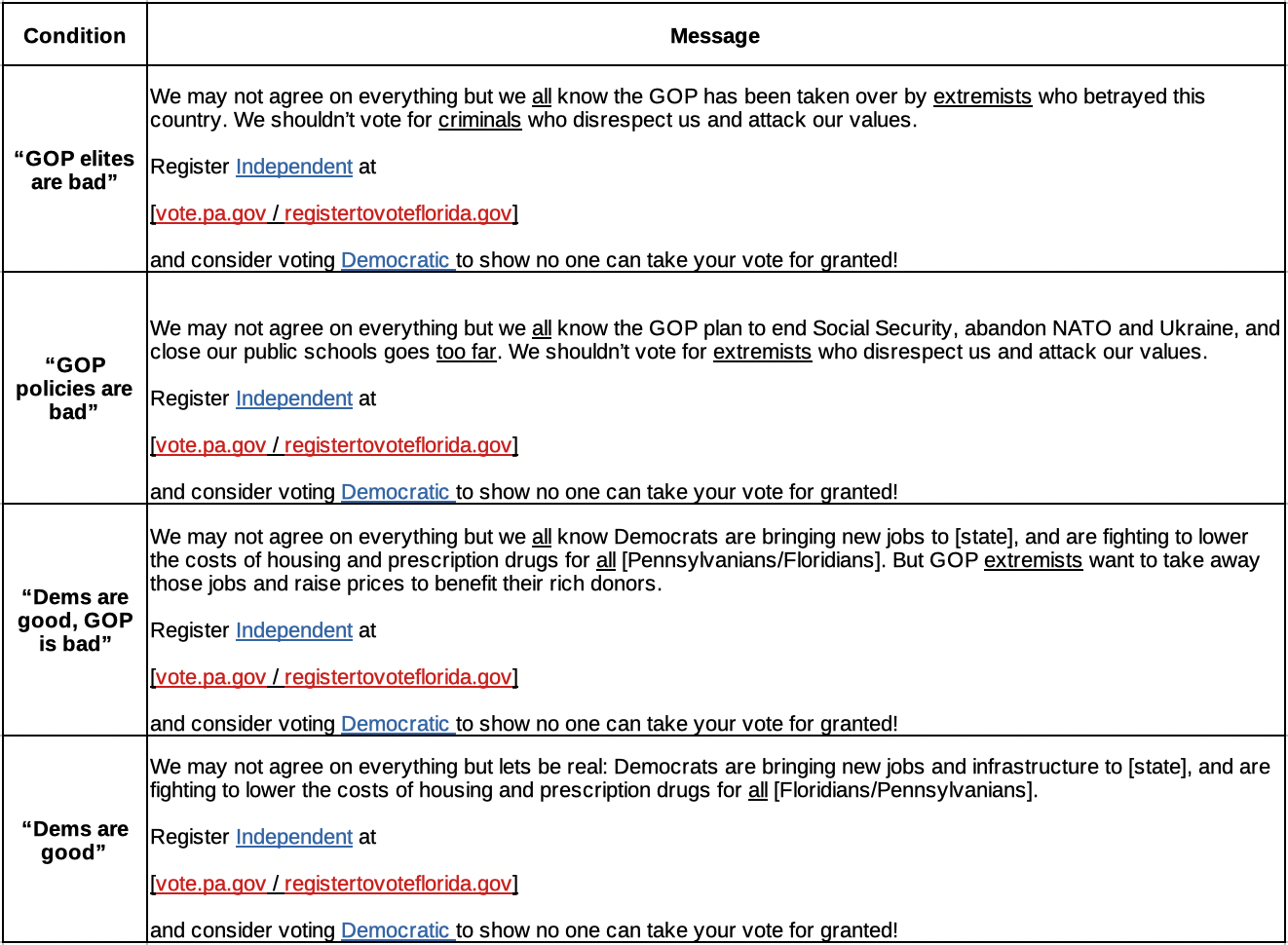

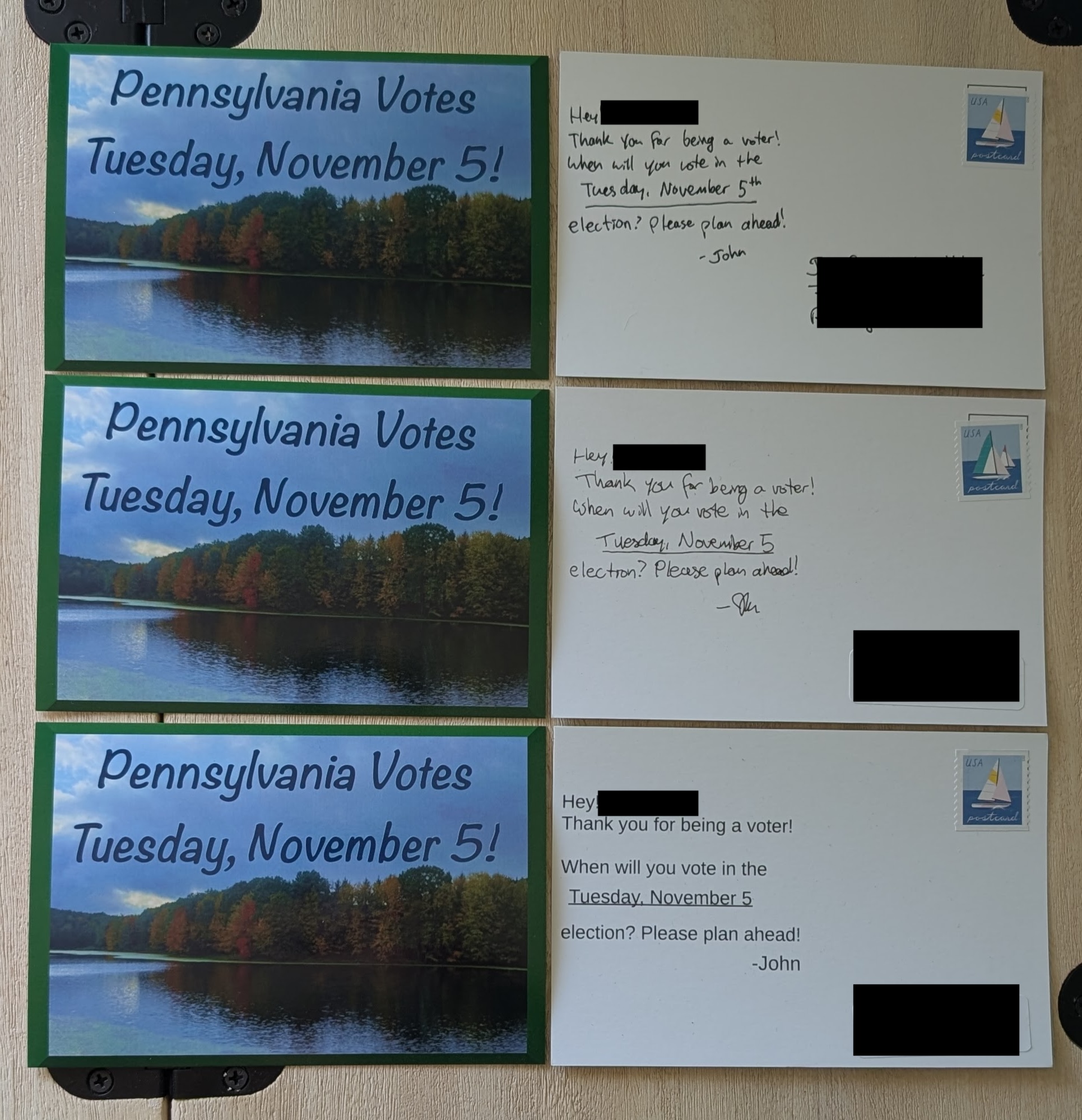

Within that sample universe, I randomly assigned about 1,600 voters into one of four messaging conditions in each state (which ended up at n=1,603 in Florida and n=1,613 in Pennsylvania, as in each condition I wrote a couple extra) for a total of 3,216 postcards. In each condition, voters received a postcard containing one of four possible messages. More details about my motivation and the design procedure for these postcards is available at the original post. The message conditions were as follows:

Below, these conditions will be referred to as the “GOP Elites-” condition (“GOP elites are bad”), “GOP Policies-” (“GOP policies are bad”), “Dem+, GOP-” (“Dems are good, GOP is bad”), and “Dem++” (“Dems are good”).

Each message asks the respondent to reconsider their political affiliation - specifically to consider re-registering with a nonpartisan affiliation. The messages included different versions of pro-Democratic party statements, anti-GOP statements, or both. The postcards were sent out in the fall of 2024, with a confederate in each state confirming receiving postcards embedded with the treatment postcards on October 5, 2024.

Postcards to lower-turnout Republican voters did not significantly reduce Republican turnout nor induce Republicans to change their party affiliation, with no significant variation either comparing all postcard recipients (n=1,603 in Florida, n=1,613 in Pennsylvania) to control observations within the sample geography with the same sampling criteria, nor comparing control observations to each of four messaging conditions (each about n=400 apiece). Results are marginally in the direction one would expect from prior experimental and theoretical work - with the “contrast” condition producing a statistically marginal result in the expected direction and the “pro-Democrats” condition producing a statistically marginal backlash, but no results from this experiment produced statistically significant differences from the party switch and turnout rates of the control condition.

In the Florida sample, about 2.6 percent of low-propensity Republicans changed their party affiliation between October 2024 and May 2025. About two-thirds of that change was to “No Party Affiliation,” and about one-third was to the Democrats. This was true whether or not voters received one of these postcards.

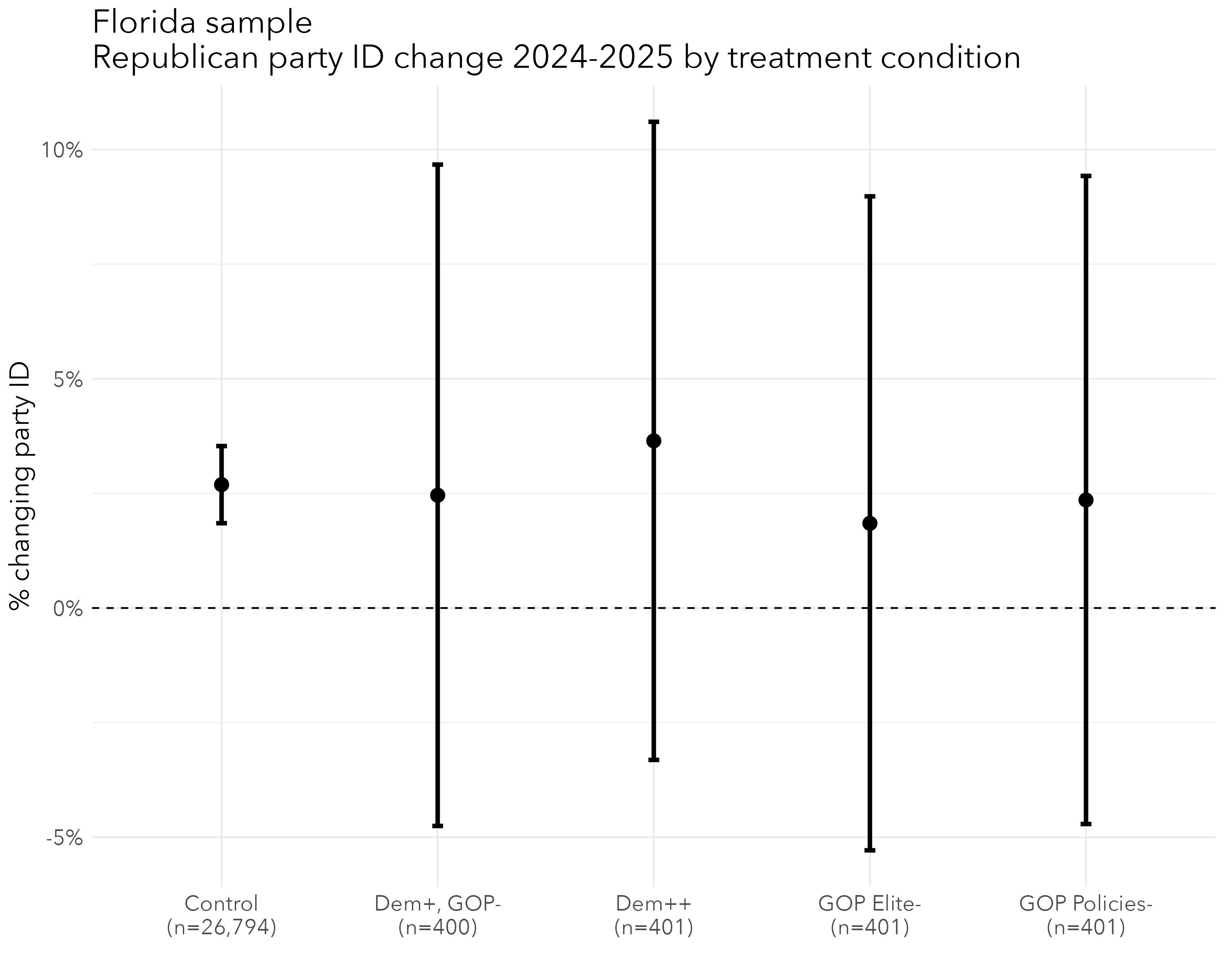

The share of voters within the sample universe, regardless of specific messaging condition, who changed their party identification was not statistically distinguishable from the rate in the control condition. This is also true comparing the control condition to each messaging condition in the Florida sample.

| Condition | Mean | N | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive postcard | 2.7% | 26,794 | 0.8% |

| Dem+, GOP- | 2.5% | 400 | 7.2% |

| Dem++ | 3.7% | 401 | 7% |

| GOP Elite- | 1.9% | 401 | 7.1% |

| GOP Policies- | 2.4% | 401 | 7.1% |

With only marginal variation across messaging condition, none of these results differed from the control condition.

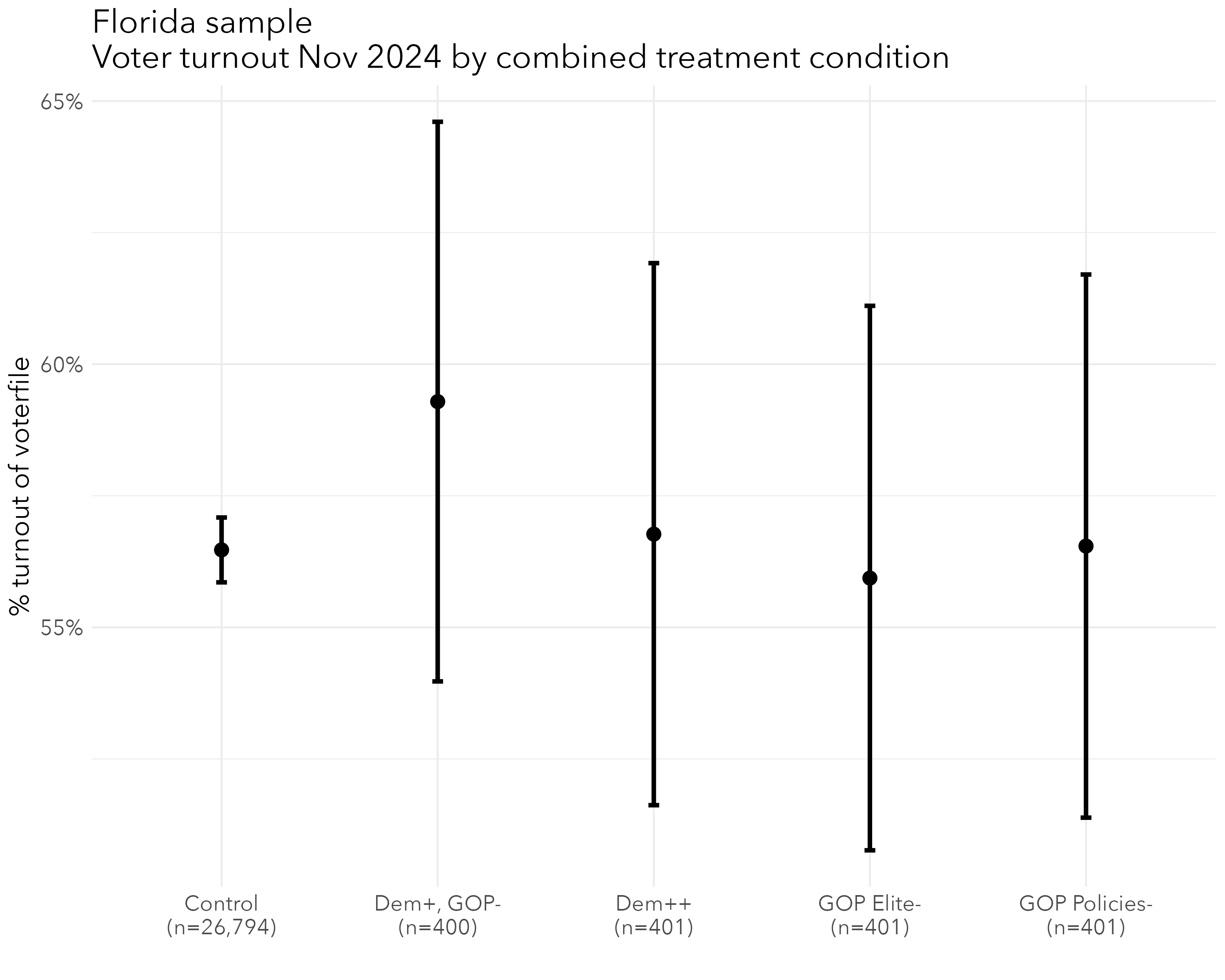

Similarly, the turnout differences among voters in Florida did not differ across control and treatment groups. Overall, about 57 percent of voters in this condition turned out to vote in 2024 (which, indeed, is low overall considering this is registered voters).

| Condition | Mean | N | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive postcard | 57% | 26,794 | 0.6% |

| Dem+, GOP- | 59% | 400 | 5.3% |

| Dem++ | 57% | 401 | 5.2% |

| GOP Elite- | 56% | 401 | 5.2% |

| GOP Policies- | 57% | 401 | 5.2% |

In each messaging condition, across two outcomes of interest, there were no statistically detectable impacts on low-propensity Republican voter behavior in 2024 in the Florida sample from the postcards sent in this experiment.

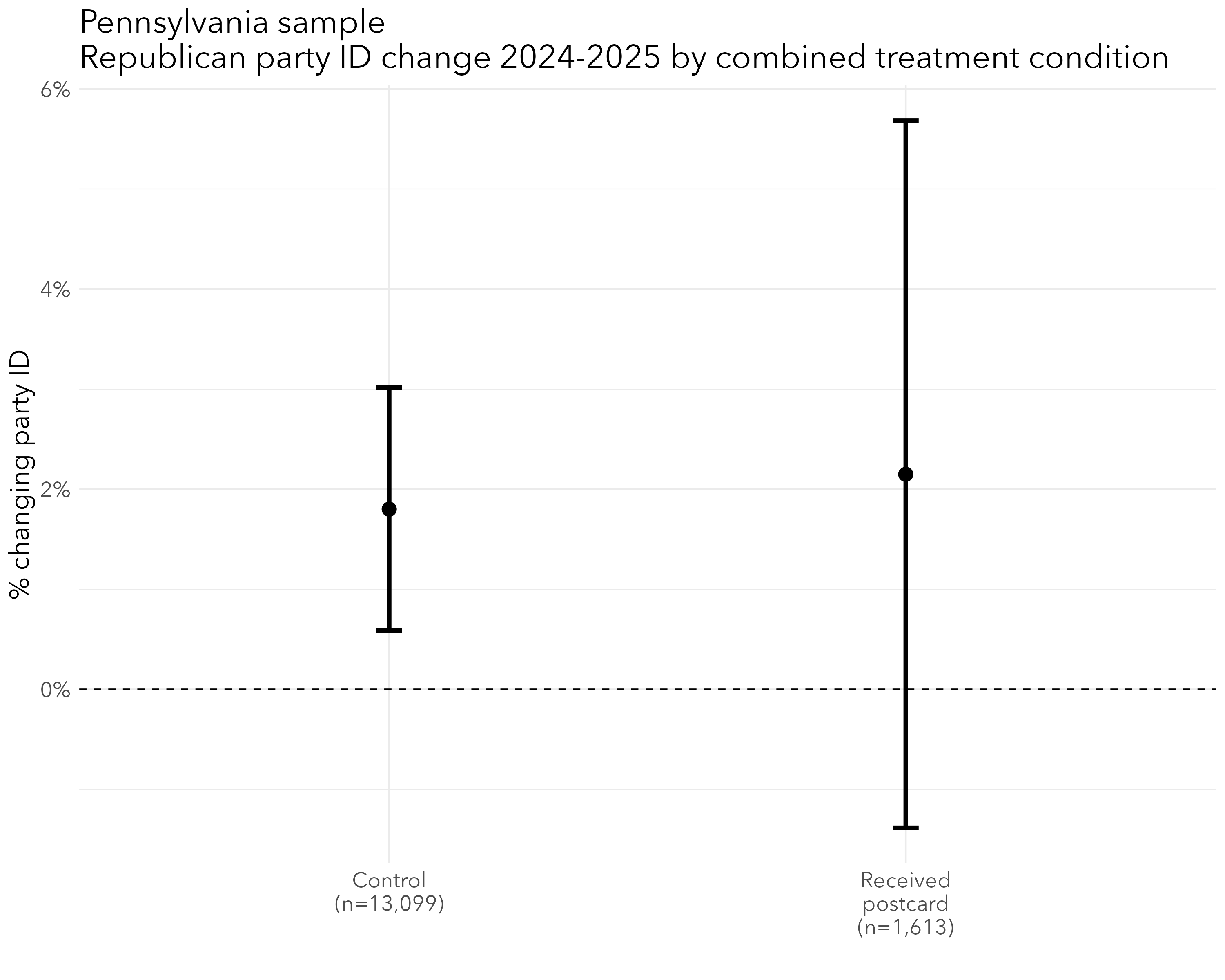

The same general set of results held in the Pennsylvania sample. The share of voters in this sample in Pennsylvania who changed their party ID in 2024 was slightly lower than in Florida - about 1.9 percent in Pennsylvania compared to about 2.6 percent in Florida. There was little variation in this outcome across the control and combined treatment conditions.

| Condition | Mean | N | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive postcard | 1.8% | 13,099 | 1.2% |

| Received postcard | 2.2% | 1,613 | 3.5% |

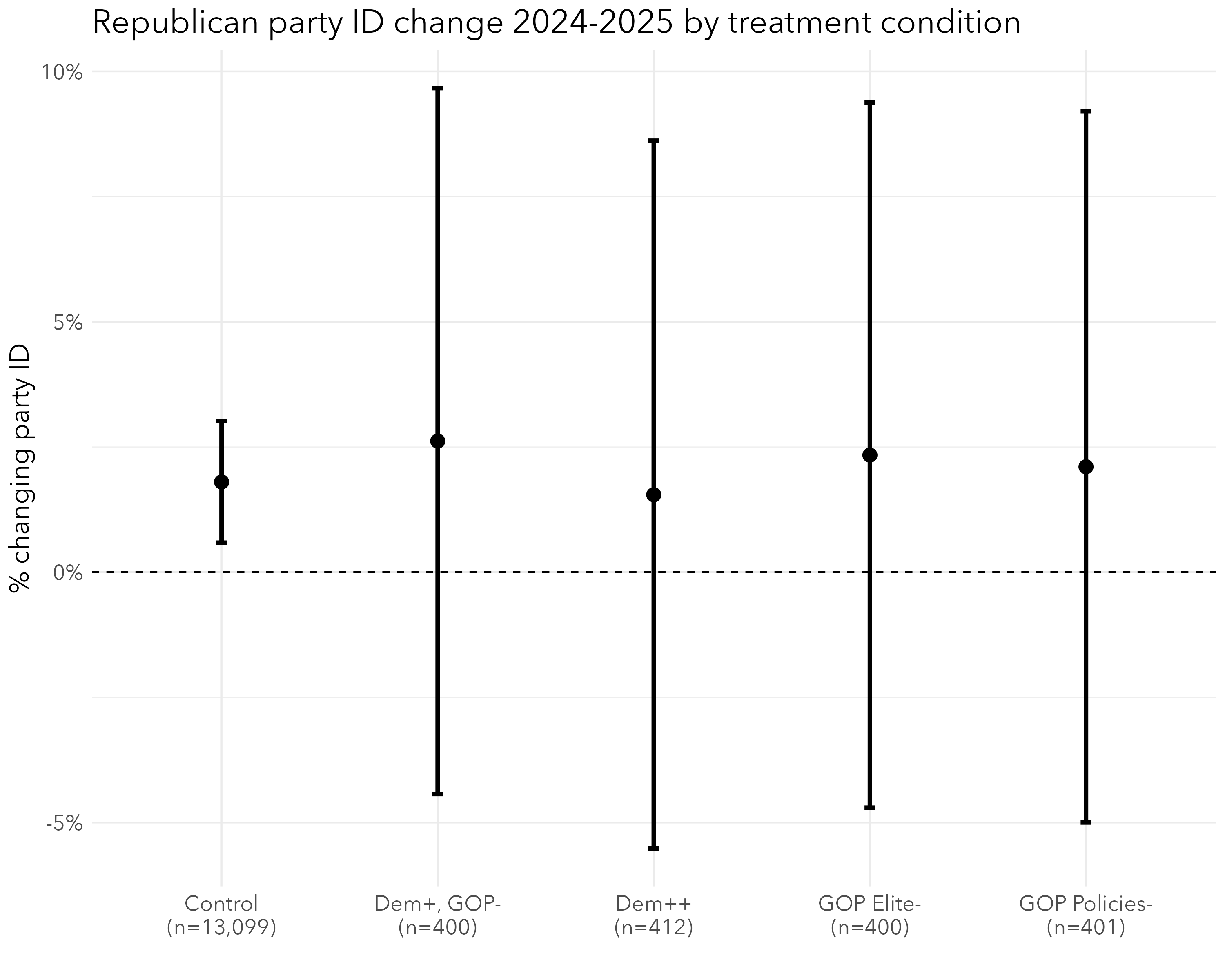

This is also true comparing the control to each messaging condition. Pennsylvania voters who received postcards were no more or less likely to change their party affiliation than voters within the same sample geography and met the same sampling criteria who did not. This remained true regardless of the message written on the postcard.

| Condition | Mean | N | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive postcard | 1.8% | 13,099 | 1.2% |

| Dem+, GOP- | 2.6% | 400 | 7% |

| Dem++ | 1.6% | 412 | 7% |

| GOP Elite- | 2.3% | 400 | 7% |

| GOP Policies- | 2.1% | 401 | 7.1% |

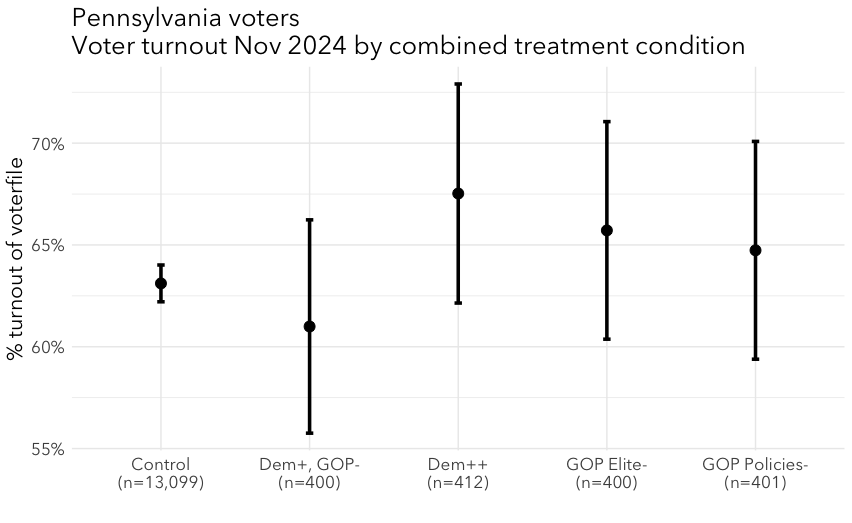

In addition to having no impact on voters’ party affiliation, these postcards had no impact on the propensity of Pennsylvania voters to turnout. In one condition, the “Dem++” (pro-Democratic message, no criticism of the GOP), the postcards got the closest among the various tests in this domain to producing a statistically discernible backlash effect. The result in this condition did not differ to a statistically significant degree from the control mean (67.5 percent turnout in the “Dem++” condition versus 63.1 percent in the control condition). Ultimately, none of the treatment effects differed significantly from the turnout rate observed in the control condition.

| Condition | Mean | N | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive postcard | 63.1% | 13,099 | 0.9% |

| Dem+, GOP- | 61% | 400 | 5.2% |

| Dem++ | 67.5% | 412 | 5.4% |

| GOP Elite- | 65.7% | 400 | 5.3% |

| GOP Policies- | 64.7% | 401 | 5.4% |

Across four different messaging domains, across two states, with two key outcomes of interest, the postcards to Republicans sent in this experiment produced no statistically significant differences from the same outcomes as measured in each test’s control condition.

Experiment 2 results: Postcards to low-turnout Democratic voters in Florida and Pennsylvania swing districts

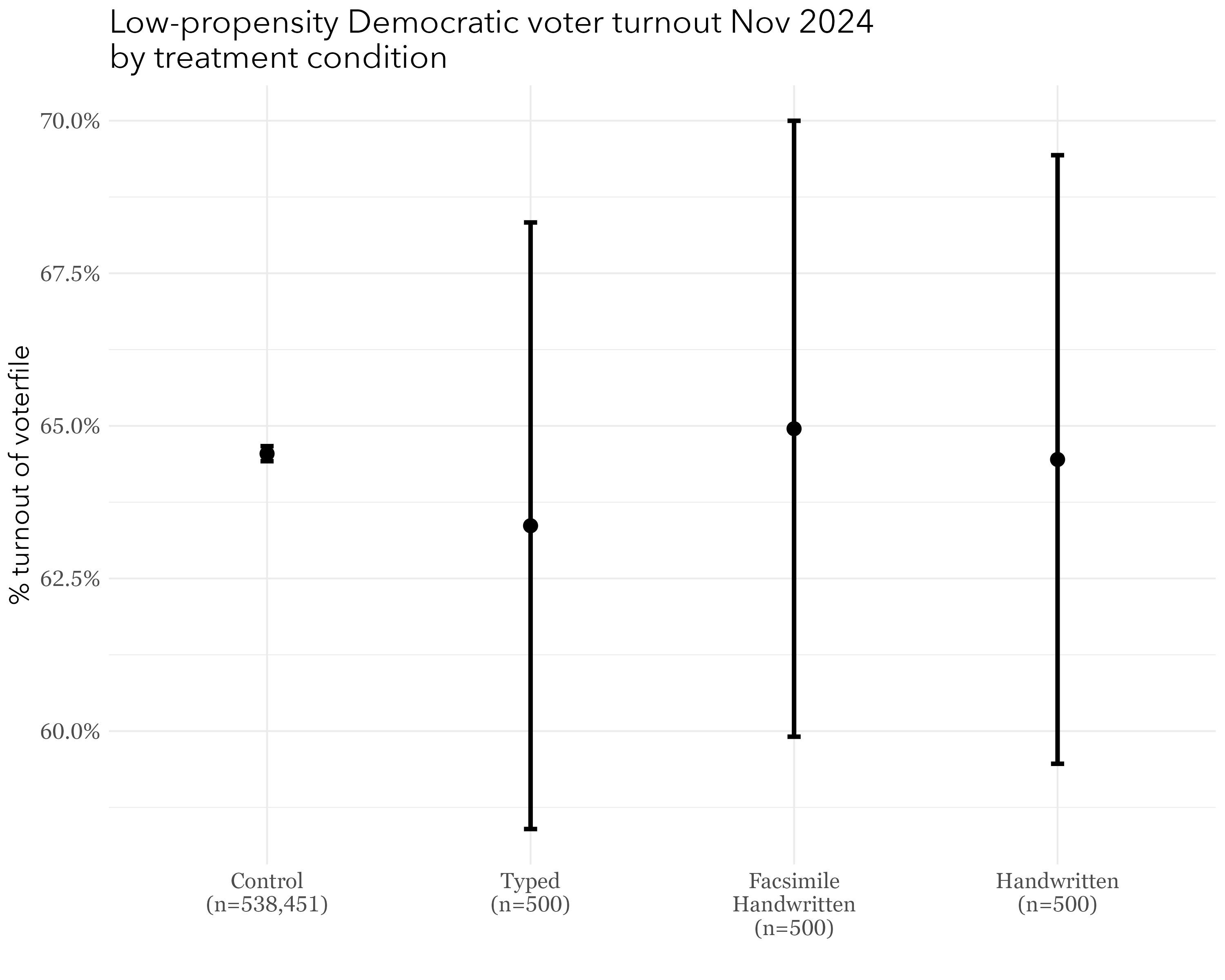

I observed no statistically significant differences between sending handwritten, typed, or “facsimile handwritten” postcards (i.e., with handwritten messages printed onto the postcards) to encourage turnout among low-propensity Democratic voters in Pennsylvania (n=1,500). Those who received any postcard, or any particular type of postcard, were no more or less likely to turn out to vote than were holdout observations within the sample geography.

I drew a sample of 1,500 low-propensity Democratic voters in Pennsylvania. In this experiment, “low-propensity Democratic voters” meant they were

- Active on the Pennsylvania voterfile

- Registered Democrat

- Did not vote in at least one of the 2016 and 2020 general elections - i.e., skipped both, skipped just 2016, or skipped just 2020

- Did not vote in primaries, with this definition using a cutoff of not having voted in any primary in the last ten years

- Was registered to vote in a precinct that in the most recent election provided majority support to at least one of the Democratic candidate for Congress, State Senate, or State House (mostly to ensure the registered Democrat had a reasonably high probability of voting Democratic should they vote)

From there, voters were randomly assigned into one of three treatment conditions:

- Receive a postcard with a handwritten message urging the recipient to vote

- Receive a postcard with a print of a handwritten message (i.e., a facsimile handwritten message) urging the recipient to vote

- Receive a postcard with a typed message urging the recipient to vote

With an example of each provided below:

These postcards were sent out on October 22, 2024, with a confederate residing in Pennsylvania confirming receipt of an embedded test postcard on October 27.

Ultimately, the typed postcards were marginally less effective at inducing turnout, while the handwritten and facsimile handwritten postcards were equally effective - with none producing a statistically significant difference from the turnout rate of the control observations.

| Condition | Mean | N | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive postcard | 64.5% | 538,451 | 0.1% |

| Typed | 63.4% | 510 | 5% |

| Facsimile Handwritten | 65% | 508 | 5.1% |

| Handwritten | 64.4% | 510 | 5% |

The results suggest that different “authorship modalities” (i.e., typed versus handwritten versus copies of handwriting) of postcards do not produce differential effects on the behavior of low-propensity Democratic voters, and that the effects of these postcards are statistically indistinguishable from receiving no postcard. There is virtually no apparent difference in voter behavior whether a voter received a handwritten or a copy of a handwritten postcard - and neither differed much from receiving no postcard at all.

Conclusion

These results are not dissimilar from what I’ve seen of several postcard program results presented in the progressive ecosystem since 2024. In total, I put together a set of field experiments that took no more than a few months of writing (and stamping, and stickering) and a budget that in total did not surpass $3,000 out of pocket. Some organizations sent out hundreds of thousands of postcards in similar efforts - many of them reporting similarly minimal effects.

Postcard campaigns were a ubiquitous part of political activism throughout 2024, with some organizations boasting that they’d sent millions of postcards, saturating voterfiles and turnout tranches and key segments. (Whether I should’ve received a postcard from a campaign I knew was targeting “low turnout Democrats” here in Texas, such as I did in September, is a bit of an open question) Now that the state voterfiles have been updated to reflect 2024 more organizations are going to be analyzing the results of their various campaigns and reflecting on them.

No one can doubt that politics - especially Presidential general election politics - is a game of inches. No one should expect there to be a “killer app” for voter turnout or persuasion in any cycle, any geography, any subset of the population - indeed, this wouldn’t be much of a Republic if thats how human behavior worked. I am as relieved to have failed to detect an implausibly large effect from a small-n experiment as I am disappointed to have observed, across a variety of population subsets, geographies, and messages, that this extremely common element of progressive campaign strategy yields such minimal effects - which others, who spent far more time, energy, and money on much larger, more comprehensive designs are learning as well.

For my part, I think I’ve written my last postcard. Further, I think organizations that will continue to ask for volunteer time, effort, and money (many of them put the postage burden on the volunteer) are on the hook to explain why. These results suggest you could just as well ask someone to write one postcard and then copy it onto many others with no loss of effect (if there is an effect at all). Perhaps more seriously, the raft of experimental results on this subject rolling out over this spring from the many groups that used postcards last cycle suggest it may be time to reorient to other ways to make use of volunteer time.

If you’ve ever participated in postcard events, you probably already know where I’m going with this. In my experience, writing a large number of postcards can get to be pretty excrutiating. And I don’t mean just at the extreme end of the kooks among us who take it upon themselves to send out over 3,000 postcards themselves. Many political activists are in retirement, putting them in a place where writing what amounts to pages and pages of text by hand can get pretty uncomfortable. Many others are young enough to find it a bit absurd to think that a postcard could have much impact when they are generally not in the habit of checking physical mail themselves.

What if these countless activists, instead of spending an evening writing postcards by hand, engaged in more intimate forms of relational contact to people in their own social networks? What if they were taught how to use the social media platforms most frequented by lower-engagement voters like TikTok and Insta? What if we put more resources and energy into making ourselves seen on YouTube? What if we simply had house parties and barbecues for their own sakes, inviting our less politically wonky friends to come along and split a bottle of wine and kvetch about what matters to us, no handwriting chores to complete strangers necessary? We can all imagine new and interesting ways to make our voices heard, and if your answer to the 2024 cycle is to assert that the best use of a dedicated activist’s time is producing twenty postcards over the course of one entire weekend evening of the limited number of such occasions an election cycle provides, I would love to hear why. In the meantime, I’d rather start cracking on some competing offerings for people who, like me, are looking for other ways to participate.

I believe Hal Malchow’s parting advice continues to be among the most urgent elements of the progressive research agenda this cycle and beyond - the advice that

Polling suggests that party-allegiance is more fluid than many would suspect… Surely, if we can convince one voter to become a Democrat, that conversion might benefit candidates in more than one hundred races as opposed to our current strategy of contesting one election.

How much will it cost to change a party allegiance? No one knows. But if we test this proposition we can know. And we can allocate that cost over several races and not just one. Maybe this is not a sound approach but if it works it will influence many more election outcomes over a longer period. We will never know whether advertising for party is a good strategy until we put it to the test.

and I will continue to pursue this agenda. The two most important things for a data practitioner to do are 1) figure out what data to trust, and 2) listen to it even when they don’t like what it has to say. These results tell me its time try something else. Ultimately, this is perfectly fine by me - by October, I was pretty damn tired of writing postcards - so stay tuned. On to the next thing.