In the classic Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk (1979), Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky report the results of several experiments consistent with a then-novel theory of how humans make decisions. They called their theory prospect theory, as it pertained to how peoples’ behavior changed depending on whether they were facing positive or negative future prospects. One of the paper’s many key insights is this: in expectation, a typical person’s value function is generally concave with respect to gains and convex for losses, suggesting that “losses loom larger than gains” in terms of how they may impact peoples’ happiness. They illustrate the argument with a hypothetical value function like so:

(there have been some advances in data visualization in the decades since, but you get the idea)

The paper’s experiments suggest that, for the typical person, losses will hurt more than equally-sized gains will feel good. In practice, the authors suggest this means people will take more risks to avoid losses than they will to achieve gains. Facing an equally-sized potential future loss or potential fugure gain, people will be more willing to make risky decisions to potentially decrease the size of the loss than increase the size of the gain.

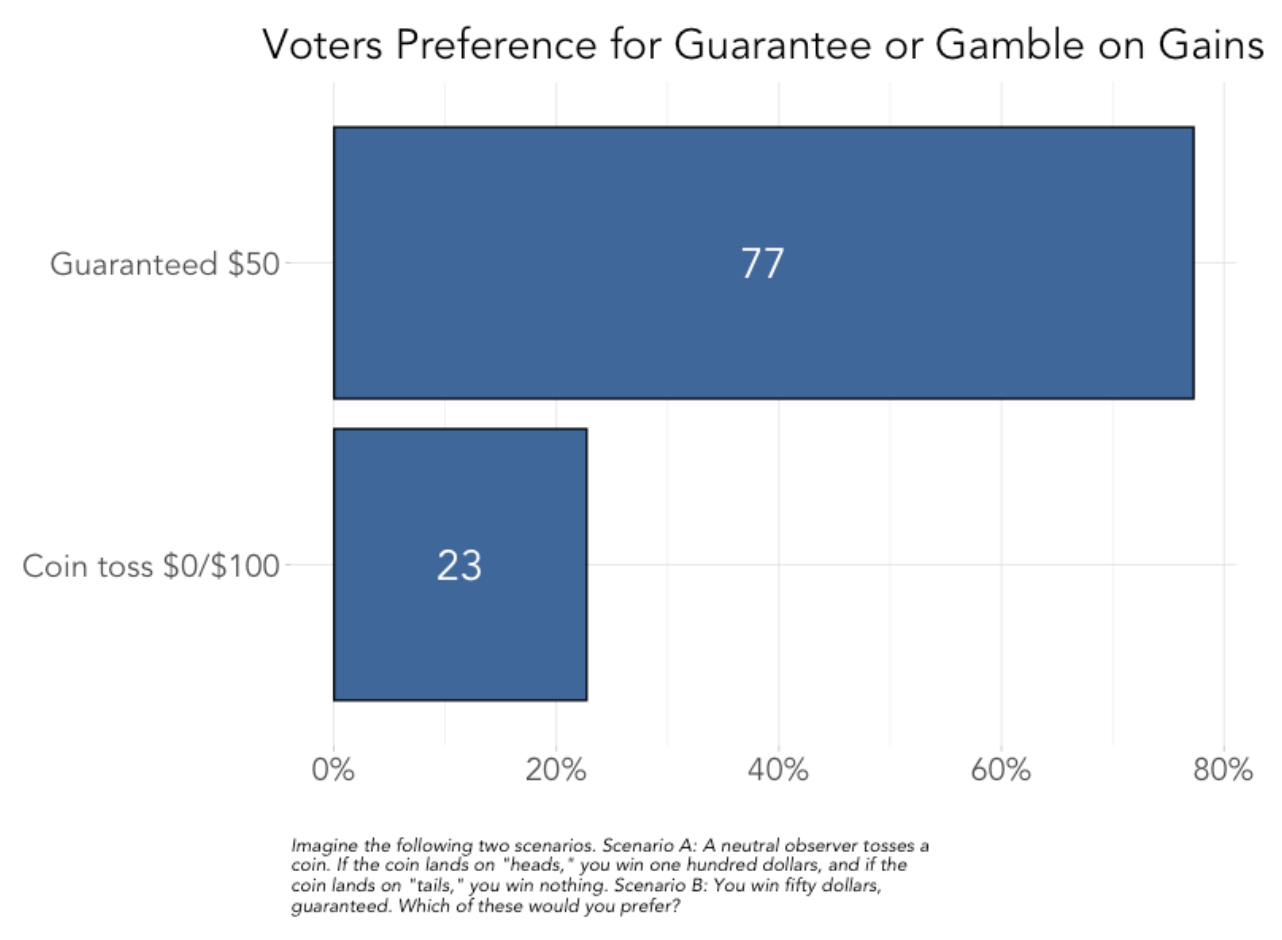

I replicated a couple of the paper’s results on a recent YouGov survey, which fielded March 7-8, 2024 on a sample of 1,012 US voters weighted to the registered voter population. Specifically, I asked people to consider the following two scenarios:

Scenario 1 (gains)

- Choice A: A neutral observer tosses a coin. If the coin lands on “heads,” you win one hundred dollars, and if the coin lands on “tails,” you win nothing.

- Choice B: You win fifty dollars, guaranteed.

Scenario 2 (losses)

- Choice A: A neutral observer tosses a coin. If the coin lands on “heads,” you must pay one hundred dollars, and if the coin lands on “tails,” you pay nothing.

- Choice B: You must pay fifty dollars, guaranteed.

Take a moment and think about which choice you’d prefer in each scenario!

Overall, in Scenario 1 about three-quarters of voters prefer the “sure thing,” the guarantee of fifty bucks.

On the other hand, among those same voters, about three quarters of voters prefer the “gamble” to try and avoid the loss.

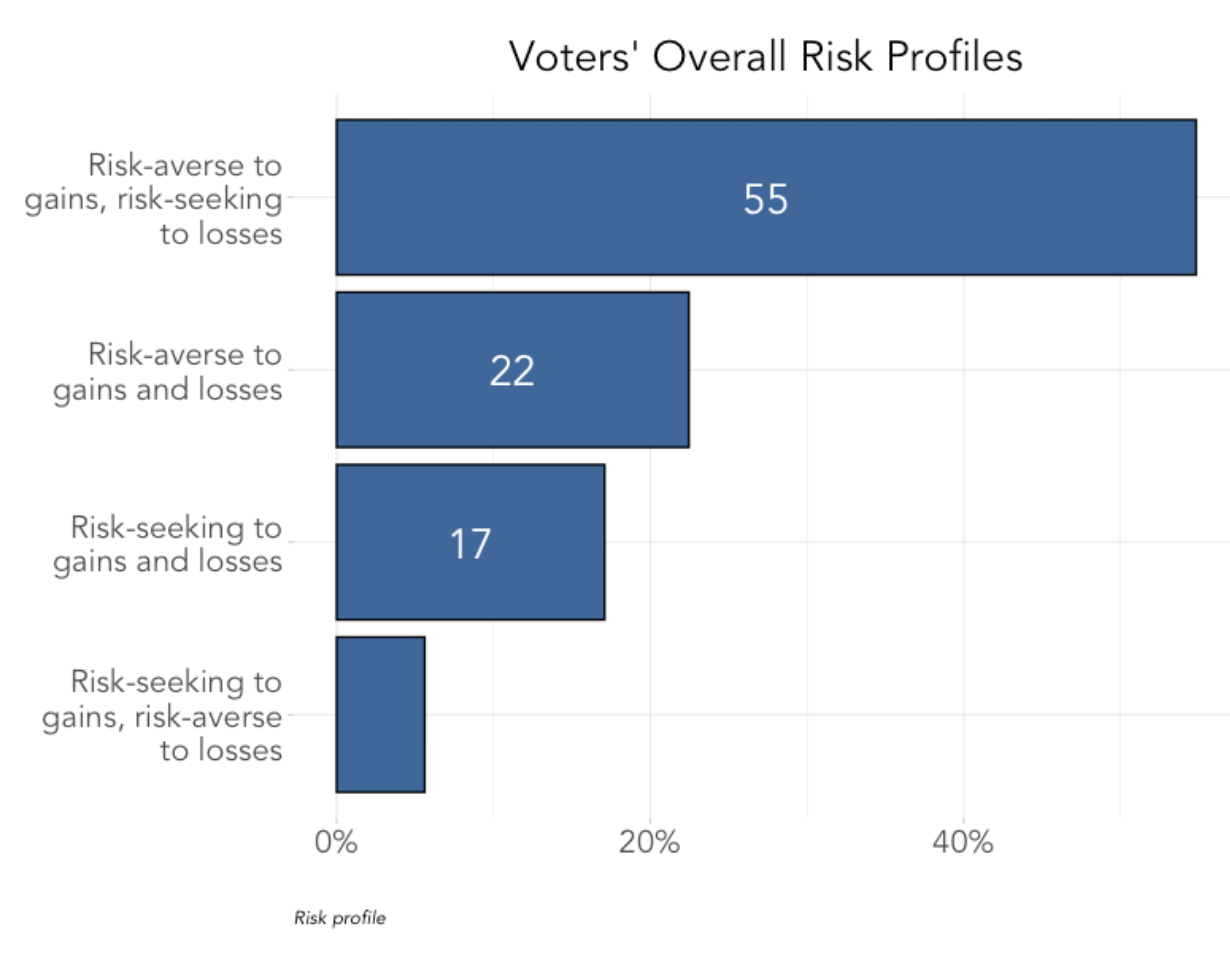

These preferences defy partisanship. About 79 percent of Democrats prefer the “sure thing” when it comes to the prospect of gaining money compared to 21 percent who prefer the gamble, as do Independents by a 78-22 margin along with Republicans by 75-25 margin. Similarly, 74 percent of Democrats prefer the gamble in the losses scenario compared to 26 percent who prefer the sure loss, along with a 69-31 split among Independents, and a 71-29 split among Republicans. Regardless of political leaning, most voters are risk-averse with respect to gains and risk-seeking with respect to losses.

Combining voters’ choices across both scenarios, an outright majority of voters follow the general prediction of prospect theory. About a quarter of voters preferred the risk-averse option in both cases, and about a quarter of voters preferred the risk-seeking option in both cases. (A statistically negligible share of voters had the opposite preferences of what prospect theory predicts, about 5-6 percent of the sample)

The majority of voters say they will take a risk to avoid a loss in the future, but will forego the prospect of a risky but potentially larger gain in order to guarantee they get a smaller gain. These preferences cross partisanship.

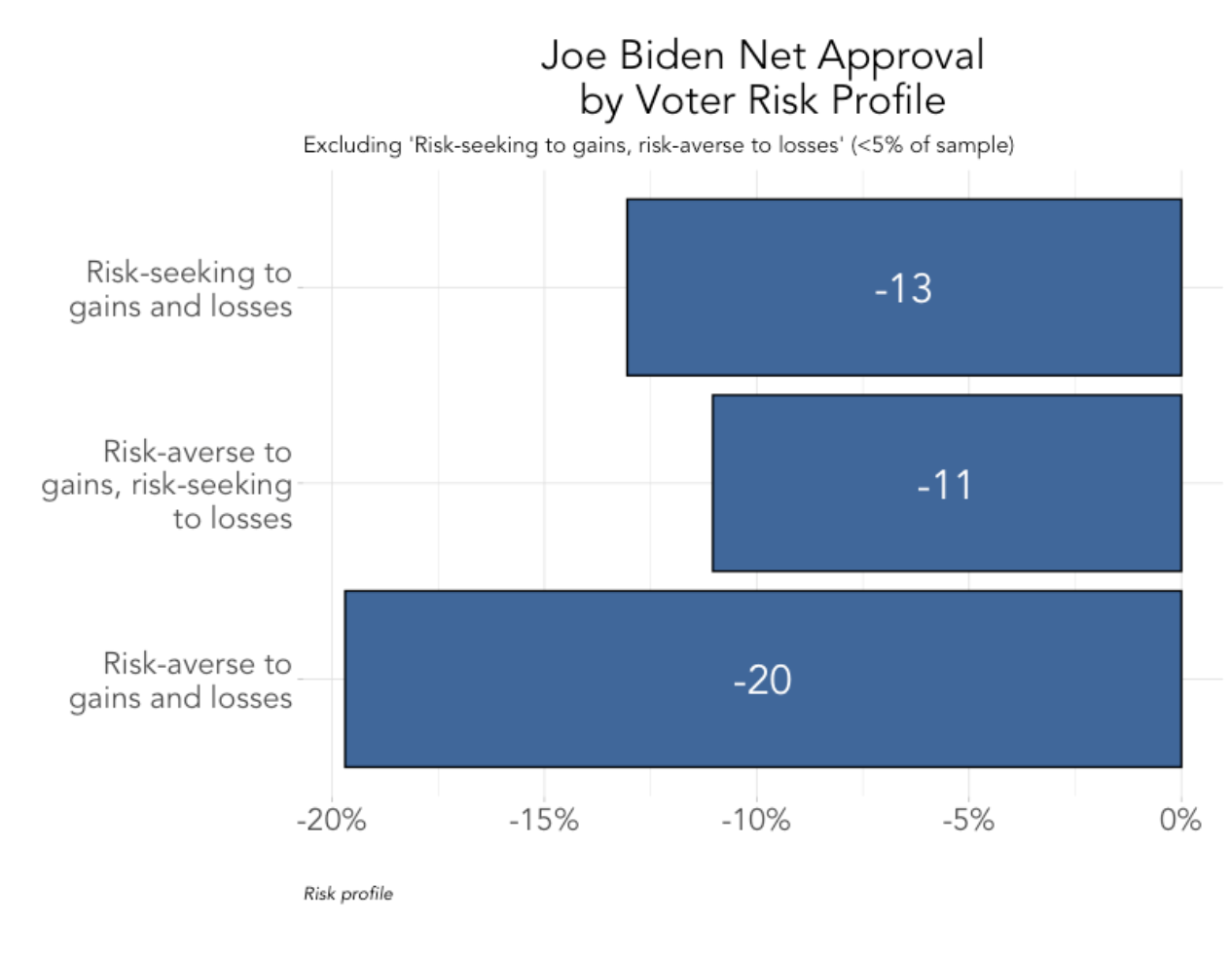

These preferences correlate with other key attitudes voters hold about the state of the world. Many have wondered why, when the economy is currently so good, pessimism about the direction of the country is so high. Bearing in mind that these risk preferences are cross-partisan, I think breaking out voters’ risk preferences by their overall views of the state of the country is illustrative: While pretty much everyone is pessimistic overall on the current state of the country, those who are most tolerant of future risk are about 15 percentage points or so less pessimistic about where the country is headed than those who are more risk-averse.

Those who are willing to gamble both to secure larger gains and avoid larger losses are the least pessimistic about the current direction of the country. One reason the spread between the risk-seeking and the risk-averse may currently be large is if people generally think the future is very uncertain, those who are more tolerant of uncertainty are less put off by the idea of a future with risky but potentially good prospects (bearing in mind this is a distinct minority of voters!). And again noting that these risk preferences are distributed similarly across partisanship, those who are currently most tolerant of future risk are also currently the most approving - er, least sour - on Joe Biden, measured using a standard job approval item:

I believe there is some important messaging advice in all this. Voters say they will take riskier actions if they believe the alternative is a sure negative in the future - but they also say they won’t take similar risks when it comes to gains. Voters will gamble to avoid the negative, but will prefer assurance when it comes to the positive - and will pay a “risk premium” to get it, trading potentially larger gain for a smaller “sure thing.”

To me, this suggests voters need to hear about how policies will protect the future as a “sure thing” that will ensure a clear and positive outcome – not that they are astounding or novel. (Indeed, some of Democrats’ most popular policies are literal insurance policies, and most of Republicans’ least popular policies are the radical changes they have made to healthcare, to income inequality, etc.) At the same time, voters who believe the future is going to be very bad are probably going to be more likely to endorse risky decisions. It may be possible to speak to this sort of pessimism by promising to assure, ensure, and insure. Framing policies as reliable opportunities rather than as miracles in waiting may be more appealing to a large share of voters. Voters who believe we are facing certain doom will be more willing to take big risks than they would otherwise.

Voters’ preferences are relatively clearer when we’re talking about monetary gains and losses and I’ve increasingly been trying to help people speak in these terms. I believe successful policy advocacy tends to include a clear, concrete, and relatively immediate benefit to those who come to be persuaded on its basis. (This has forced me to rethink how we advocate for more high-minded goals, but I think we can do it!) People can only be rationally expected to support something, from a single policy to a grandiose vision of our political system, to the degree to which they believe they will benefit in some tangible way.

To some, this leads to rather boring advice – be disciplined about, and sympathetic to, immediate economic concerns. I stand by this advice. I also stand by the prime importance of understanding how people are framing their personal vision of the future, as this goes a long way in helping you understand how to communicate with them. It is harder to tell someone not to make a bad choice if they already believe all the other choices are bad. People need assurances, and realistic assurances at that, that they can easily roll into their own vision of the future. People respond to a positive vision of the future that has clarity, certainty, and immediacy.

How do your ideas speak to voters’ personal material conditions, provide a bulwark against the volatility of the future, and assure voters that things will improve in a clear and comprehensible way? This is the type of positive vision of the future I believe people need to see in order to believe in something.